I think one of the biggest challenge for system engineers is designing security. Recently, at the 32c3 conference, plutoo, derrek, and smea presented a series of hacks that completely defeated the security of the 3DS. As a result, people have implemented boot-time unsigned code execution (called “arm9loaderhax” in the 3DS community; other communities might relate this with ”untethered jailbreak” or “bootloader unlock”). What I want to do today is not to reveal anything novel, but look at the security of the 3DS as a whole and see what went wrong. In this deep dive, I will hypothesize the design decisions that led to the cryptosystem found on the 3DS. Then I will present the flaws that led to “arm9loaderhax.” Finally, I will summarize the findings and provide a few tips to fellow engineers in hopes that these kinds of mistakes will not be made again. (Extra details are provided in parenthesis, they are for people with deeper knowledge of the 3DS and are not required to understand the rest of the article.)

Preliminary

Let’s begin with the first question that ought to be asked when designing a secure system: what is the threat model? I believe that for Nintendo, it boils down to two things

- System integrity: all code running on the system should be checked and signed by Nintendo. This ensures that users are safe from malicious code and that Nintendo gets licensing fees from games and applications.

- Content protection (DRM): code and resources should not be extractable by the user. This protects license holders (creating trust in the system) and ensures intellectual property cannot be stolen by competitors.

Note that the threat model takes account of factors that directly impact business. I’m sure there’s also other points considered (prevent cheating, protect user privacy, etc), but once you know what the most important assets are, you have a better understanding of how to protect them. These take priority. Of the two points listed, which is the most important? You might argue DRM because that’s where most of the money lies (and I think Nintendo did too). However, we will soon see that without system integrity, you cannot even toy with the idea of DRM.

System Integrity

In order to ensure all code running on a system is authorized, there needs to be a trust hierarchy. An example of this is: userland code always trusts kernel code, but kernel code has to cryptographically verify user code before running it. Now who verifies kernel code? The kernel loader. And so on… This process ensures that every component of the system has been audited by some other component.

On the 3DS (as with most systems), the boot ROM is the root of the trust hierarchy. The code there cannot be changed, and contains root cryptographic certificates (public keys).

On the 3DS (as with most systems), the boot ROM is the root of the trust hierarchy. The code there cannot be changed, and contains root cryptographic certificates (public keys).

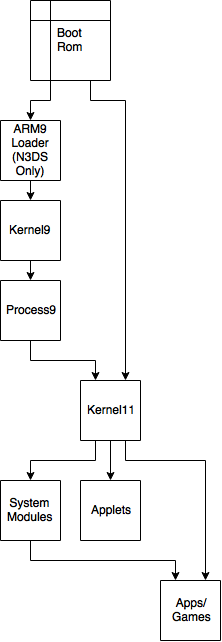

There are two processors on the 3DS. The ARM9 “security” processor facilitates crypto (access to key generator, AES/RSA engines, etc), file system access to the NAND, and other low-level stuff. The ARM9 processor talks to the ARM11 processor through Process9 (user mode on ARM9) which ideally does security checks and then talks to Kernel9. (However, if you watched the 32c3 talk linked to above, this isn’t necessarily the case as Kernel9 has a system call that is literally “run whatever code you pass in.” Therefore, the diagram on the left is actually wrong as Process9 is not separated from Kernel9 at all.) We will look at the ARM9 Loader later.

The ARM11 “application” processor is the CPU that does everything you see. I go into more details about how modules are loaded in my last article, but the gist of it is that there are kernel calls that only certain system module (running in user mode) can access. Applications must communicate with these modules to get system resources. The ARM11 kernel sometimes has to communicate with Process9 (on ARM9) to get access to more sensitive system resources.

So aside from a couple of concerns, the design of the secure boot chain is mostly solid. (Of course implementation is another story; there has been many flaws in the system software and almost no exploit mitigation.) One good design choice here is that Kernel11 has low exposure. Because the system modules does most of the work, the kernel does not have to expose all syscalls to every application. For example, a game does not have access to the syscalls to map executable memory. So, in order for an exploit found in a game to run arbitrary code, it would have to first compromise the “ro” module (which has the right syscalls). This also means that code running in supervisor mode can be more limited and smaller in size, which means that bugs would be easier to spot. Again, this is all good in theory; but in practice, some very stupid implementation flaws (allowing the GPU to write to executable memory for example) makes this all moot–a story I don’t have time to get into. Another good design choice is that complexity only grows as you move down the trust hierarchy. When there’s more code, there’s more bugs, so keeping the bulk of the complexity in less trusted code is good for security. However, this is only a rule of thumb and should not serve as a type of defense!

Content Protection

Let’s assume for now that we have system integrity (we don’t). How do we implement DRM? The truth is that DRM is impossible in theory. However, as engineers, we do not always have to follow theory. The secret of DRM is that, unlike other cryptosystems, you are not designing it to be secure forever. (Note for the pedantic: I know that no cryptosystem currently known would last forever, but if you can point out this fact, you also know what I mean.) Specifically, if your DRM can last 100 years, most people (on the engineering side) would be very happy. In fact, if you can provably do that, you would “solve” the problem of DRM. Most DRM schemes are designed with decades in mind (something that you might not admit to business people). That means we can commit some security faux pas that the textbooks would forbid. For example, security by obscurity is a tool here. If it takes the hacker 5 years to figure out your scheme, then by all means do it, because you just bought another 5 years. (But be warned that if you think it takes 5 years to crack the scheme, it likely will take 5 months.)

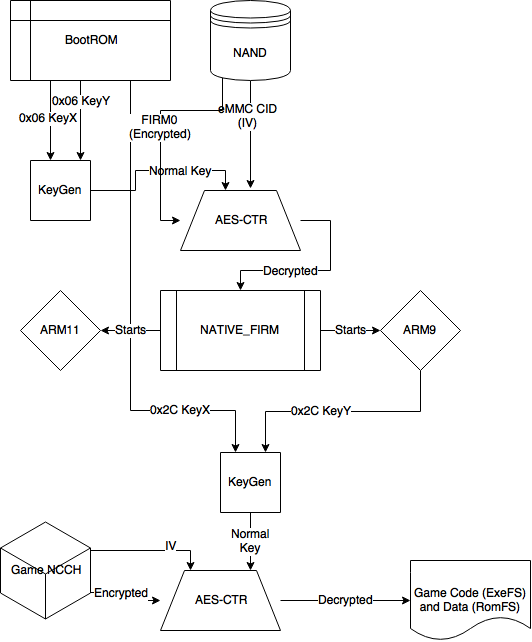

Original 3DS Implementation

First, let’s go over the crypto primitives we have on the 3DS. There is an on-chip hardware AES engine with 64 keyslots. When a key is written into a key-slot, it stays there until it’s either cleared or rewritten with another key. You can write a “normal key” into the key-slot and the AES operation works as usual (with the normal key being the key). The more interesting case is if you instead write two keys–KeyX and KeyY–into the slot. In that case, an on-chip key generator derives the “normal key.” However, the normal key is never revealed outside the AES engine! That means, even if we extract KeyX and KeyY (by dumping the code that sets them), we cannot find the normal key (… in theory, I’ll come back to this point later). There is also a hardware RSA engine that has its own key-slots and operates similarly (except there is no key generator).

Games are stored in a container format named NCCH (unnecessary details: game carts are in NCCH with an additional block level encryption on the cart. eShop games are in NCCH with an additional layer of encryption by a “title key” that is decrypted by the “common key” (key-slot 0x3D, KeyX set by boot ROM, KeyY set by Kernel9). However, these details are unnecessary because it does not change anything in the trust.) It is decrypted with a key generated from a KeyX set by the boot ROM and a KeyY set by Process9. Process9 is found in NATIVE_FIRM which is stored encrypted on the NAND with a console-unique IV. The key to decrypt NATIVE_FIRM is set by the boot ROM. The console-unique IV is derived from a (maybe not so) unique card ID found on the eMMC (NAND). This is to prevent a downgrade attack on a new console using the firmware extracted from an older, vulnerable, console.

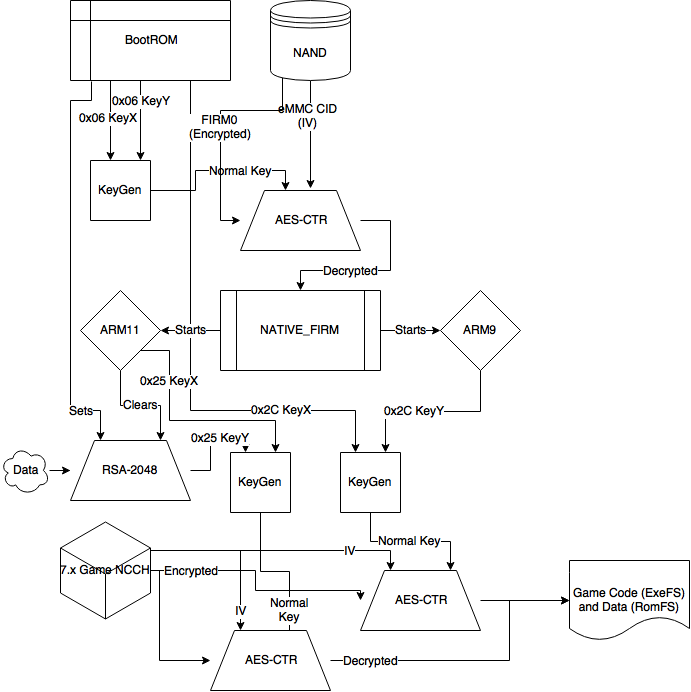

7.x Implementation

Speaking of vulnerabilities–in 2013, the first 3DS hack came out (a simple buffer overflow in Process9). This set Nintendo into something of a panic. Hackers broke the trust hierarchy at the Kernel9 level, which means that they control everything underneath that. Even though the NCCH KeyX (0x2C) was in the boot ROM and therefore still safe, hackers can use the key generator as a black box to decrypt whatever games they like. In order to protect future games from being decrypted in this way, they came up with a rather ingenious plan

In the boot ROM, the RSA engine (slot 0x0) is initialized with a key so it can be used later in the boot process. In Kernel9, slot 0x0 is used with an RSA operation and the key-slot is overwritten with another key. Just like the AES engine, once a key-slot is overwritten, it is impossible to extract the previous key. Note that it is unlikely Nintendo purposely erased this key-slot for security measures. The real reason is likely that there’s only 4 RSA key-slots (versus 64 AES key-slots), so they needed to re-use slot 0x0 for other RSA operations. The ingenious method Nintendo devised was to use some unrelated data outputted from the RSA engine at slot 0x0 to derive the 7.x NCCH KeyY. Because all versions of the firmware (including the vulnerable ones) have wiped this slot by the time the exploit could be triggered and since the boot ROM is still secured, even if you run the algorithm to derive the 7.x NCCH KeyY, it won’t work since RSA slot 0x0 has already been wiped. (In the diagram, the old NCCH key is used in conjunction. This is for compatibility–if you put a 7.x game on an older console, the game icon and banner can still show up, but you must update the system before the game can run).

Ultimately, to get these keys you need to get code execution to work before Kernel9 is first initialized (and wipes the key-slot). arm9loaderhax (described later) found in 2015 does this, but from what I understand, a undisclosed method was used to retrieve these keys originally (in 2014). However, since a 9.2 exploit was found in early 2015 (I wrote a series on it back then), the black-box method to decrypt games worked again.

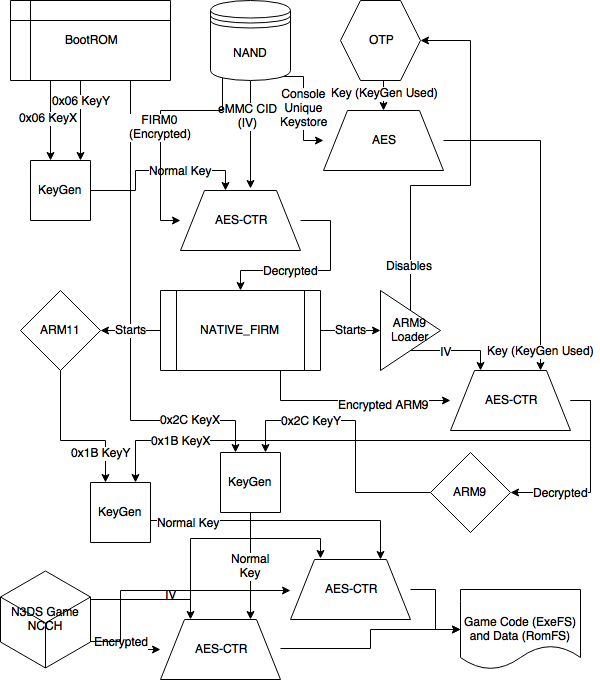

New 3DS Implementation

Near the end of 2014, Nintendo released the New 3DS–the first major hardware revision. This was also their chance to try to salvage what’s left of their cryptosystem. Sorry mobile viewers, the diagram only gets more complicated…

First, I want to introduce an element I’ve left off before because it did not affect the security then. The OTP (one time programmable) section is unique data found physically in the CPU (okay pedants, the “SoC”). Its primary use is to store a ECDSA private key for identifying the console to Nintendo’s servers (for eShop and services). It exists on the old 3DS as well but on the New 3DS, it has been integrated into the chain of trust.

The New 3DS also comes with a new key-store found in a sector of the eMMC (NAND). The data in the key-store is the same on each console, but the key-store itself is AES encrypted with a SHA256 hash of the OTP section as the key. That means that the encrypted key-store is console unique! The OTP region is disabled early in the boot process: Kernel9 on the old 3DS (but not really, more on this later…), and the new ARM9 Loader on the New 3DS. That means, if implemented correctly, it should not be possible to decrypt the key-store after boot–even if you exploit the system at a later point. (Key word: correctly. Even though the keys were wiped from the AES engine, they forgot to wipe it from the SHA engine used in deriving the keys!)

Using the new NAND key-store, the New 3DS derives keys for NCCH decryption of New 3DS-only titles. Remember, the old 3DS does not have this NAND key-store, so it would not be able to derive the new keys. It is also unlikely that there is any hope in the form of another lucky slot that’s cleared early in the boot process. That means, black-box decryption of any old 3DS supported games will always be possible. However, maybe they can still protect New 3DS only games…

The other addition is the ARM9 Loader. Previously, once NATIVE_FIRM is decrypted, the code for ARM9 and ARM11 runs on their respective processors. Nintendo now added an additional layer of encryption for the Kernel9/Process9 code and they added ARM9 Loader to derive the new keys and decrypt the new layer. I think the idea here is this: there are potentially 32 keys we can use in the NAND key-store. If someone hacks the latest ARM9 firmware and obtain the secrets there, we can always release an update that encrypts it with a new key. Since the ARM9 Loader is added to the hierarchy of trust, as long as A9L is safe (and it is a much smaller code-base than Kernel9/Process9), even if they hack Kernel9, they cannot find the new keys released in an update and must hack the firmware again to get the new secrets. This was perhaps a solution to the panic of 7.x when it was hard to re-secure secrets after the system was hacked once.

We first saw this new system put to test with firmware 9.6. Before then, Nintendo made the mistake of forgetting to clear a key-slot initialized by the OTP hash. Although the OTP hash was still safe, it was possible to derive many other New 3DS keys from access to that key-slot. This includes the KeyX/KeyY for the new encryption layer on the ARM9 code. But no fear! 9.6 encrypted the ARM9 code derived from a new key in the key-store and for almost a year people outside of a few inner circles cannot decrypt anything for the New 3DS.

Things Fall Apart

What I like about the arm9loaderhax (here-forth A9LH) is that it’s only possible because of all the added complexity in the cryptosystem. The original system I showed would not have been vulnerable. However, A9LH is inevitable because Nintendo must respond to each attack. It is just unfortunate that each hole they patch only reveals more leaks. I’m not going to go into details of how A9LH works, delebile did a wonderful writeup on it. Instead, I’ll try to answer why it works.

To do that, let’s work backwards. The finale is that because the decryption of the ARM9 code is unauthenticated, if you corrupt the key-store, a junk key will be derived and the encrypted ARM9 code will decrypt into junk data. Then the console jumps into junk data which, if interpreted as code, can branch into a controlled region of memory with our payload. Thanks to ARM’s RISC-y instruction set, a random branch instruction is easy to find.

But if we were to have performed this attack on firmware 9.5, it would have failed. In 9.5, the first 16 bytes of the decrypted key-store is used to derive key-slot 0x15. That key is first used to decrypt a control block at offset 0x40 of the encrypted ARM9 code. If the control block is all zeros, then slot 0x15 is used again to decrypt the actual binary at offset 0x800. Now on 9.6, the first 16 bytes of the decrypted key-store is still used to derive key-slot 0x15 and the next 16 bytes are used to derive key-slot 0x16. 0x15 is still used to check the control block but 0x16 is used to decrypt the binary! They forgot to check the validity of the second 16 bytes of the key-store! They either forgot to change to slot 0x16 for checking the control block, or for technical reasons, they had to use slot 0x15 there and just neglected to use a test vector with slot 0x16. Either way, the only reason this is possible at all is because Nintendo had to revoke 9.5 and use a new key.

But we would still be stuck if we didn’t have access to the decrypted keystore. We had to modify the second 16 bytes but keep the first 16 bytes intact. There were two things people exploited here to get the KeyX/KeyY for decrypting the key-store. First, as I touched upon already, is that Nintendo forgot to clear the SHA256 registers which was used to derive the keys. However, to exploit this, for various reasons beyond the scope of this article, you needed to perform a hardware attack. The other method was more insidious. Before firmware 3.0, Nintendo forgot to lock the OTP after boot! That means if you flash any firmware < 3.0 on your 3DS (which involved some trickery for the New 3DS since it was not designed to run < 3.0), it would boot normally (as the code, of course, is signed). Then you can use any of the exploits found since then, take over the system, and dump the OTP. This means the New 3DS key-store can be decrypted and all new keys (even ones not currently used) can be derived. It’s not surprising that such a hole was overlooked because back then (three years ago), Nintendo did not expect the OTP to be used in the chain of trust. The irony is that the feature designed to bring more security was the one that completely broke it.

Key Generator

Since A9L is broken, any 3DS past, present, or future can be hacked on boot. That’s the result of A9LH. (Although for the future, a new exploit is needed to trigger a downgrade to obtain the OTP. However, I also think something that modifies the eMMC CID via hardware might also be possible. EDIT: It is not possible. NAND encryption uses a unique console key along with an unique IV derived from the CID.) So system integrity is gone. What about content protection? It’s hanging by its last thread. We can always use the 3DS as a blackbox for decrypting content. However, the goal for attackers is to get the “normal” keys and be able to decrypt content offline. The key generator is the defense for this. Remember that security by obscurity can only buy you so much time? It took about four years since the original release of the 3DS for hackers to break it.

If you haven’t watched the 32c3 presentation linked at the top of this post, I highly recommend you do so, as I’m not going to give the full details here. The gist of plutoo and yellows8’s ingenious crack was that they discovered through cryptoanalysis the algorithm of the key-generator was just some XORs and rotates. They did this because there were a couple of normal keys that were “leaked.” A couple of keys that we only know KeyX and KeyY for are found as normal keys on the WiiU (needed for communication with 3DS). Another key was accidentally included as a normal key in one firmware release, and then _changed _to KeyX KeyY in the next release!

That means that if we get KeyX and KeyY, we now have the normal keys. Unfortunately, there are still a bunch of shiny keys hidden in the boot ROM (which is also disabled like the OTP after use; no mistakes found yet).

Postmortem

So what went wrong here? I want to summarize by listing some of the big mistakes Nintendo made that hopefully won’t be made by anyone again

- Focusing on content protection instead of system integrity: you cannot have one without the other. Always implement exploit mitigation when you can!

- Not having a contingency plan for when the system is hacked: no matter how secure you think your system is, you need to have a plan for when it’s broken. That way you don’t end up scrambling around and introducing more bugs.

- Too much complexity: having lots of blocks that say “AES” and “RSA” in your plan might impress the boss, but it just adds to the attack surface. Always go with the simplest plan that secures against your threat model.

- Do not change the trust hierarchy after production! Everything is built on that hierarchy. Adding/removing from it will break assumptions that you might not even be aware of.

Sources

Some of the information here is from my own reverse engineering, but the bulk of it is from information found on 3dsbrew.org. Please let me know if there’s any mistakes or anything that doesn’t make sense.

You bastard, stop giving Nintey the secrets to the hacks. How are we gonna get A9LH on the NX now??????

lol

Nintendo doesn’t listen to outsider input anyways. If they did, then I would have a good Mario Party by now.

@G-Holiday These are things they would have already known about. Its their console after all. However they cant fix it with an update, Having learned now what made the 3ds vunerable they build protections agienst that for their next console. By the time the NX comes out itll be almost 10 years older then the 3ds. 10 years in technology is a real fucking long time. This also helps out other programmers fyi

Lots of references to pedants in this article. This only encourages me to point out that I found two occurrences of “it’s” in the article where it should have been “its”. :)

Changing the CID is not enough : NAND keyXs (0x04-0x07) are console-unique, derived from the “secret part” of the decrypted OTP (the part that is wiped by the bootROM in ITCM). Also there are AES-MACs that you would have to change to perform a manual downgrade, and once again the keyXs for this MACs are derived from the secret part of the decrypted OTP.

Thanks. Grammar is not my strong suit.

Yes, I got that clarification from yellows8 a couple days ago. Changed the article to reflect it.

Oh, also I found unproper references to Kernel11: “key-slot 0x3D, KeyX set by boot ROM, KeyY set by Kernel11” -> The KeyY is set by Process9 “In Kernel11, slot 0x0 is used with an RSA operation” -> It’s Process9 which performs RSA operations. “The OTP region is disabled early in the boot process: Kernel11 on the old 3DS” -> Kernel9, not Kernel11

The ARM11 does not have access to AES, RSA or OTP registers.

Yeah, I went by memory for most of it. thanks for the corrections.

“Unfortunately, there are still a bunch of shiny keys hidden in the boot ROM (which is also disabled like the OTP after use; no mistakes found yet).”

Can you, either as an update, or as a separate article, shed some more light on the issues with dumping the boot ROM and the remaining keys. For instance, will an SRESET type hack be possible on the 3DS like was done on the WiiU?

The short answer is that the bootrom is disabled by hardware early in the boot process so by the time we have control, we cannot access it. And any reset we know how to do also resets the cores we have code execution in so resetting makes us lose the control. If we find a way to reset while keeping control of execution in some processor then it might be a way in.

No life

Very interesting, thanks !