Recently, I stumbled upon an old cable modem sitting next to the dumpster. An neighbor just moved out and they threw away boxes of old junk. I was excited because the modem is much better than the one I currently use and has fancy features like built in 5GHz WiFi and DOCSIS 3.0 support. When I called my Internet service provider to activate it though, they told me that the modem was tied to another account likely because the neighbors did not deactivate the device before throwing it away. The technician doesn’t have access to their account so I would have to either wait for it to be inactive or somehow find them and somehow convince them to help me set up the modem they threw away.

But hackers always find a third option. I thought I could just reprogram the MAC address and activate it without issue. Modems/routers are infamously easy to hack because they always have outdated software and unprotected hardware. Almost every reverse engineering blog has a post on hacking some router at some point and every hardware hacking “training camp” works on a NETGEAR or Linksys unit. So this post will be my rite of passage into writing a “real” hardware hacking blog.

BPI+

Getting access to a shell was laughably easy so I won’t even go into details. In short, I Googled the FCC ID found on the sticker and found the full schematics for the board along with part numbers of all the chips (such information is required in the FCC approval process but most companies request that it be kept confidential). Through the schematics, I found the UART console, which was nicely exposed through some unfilled port. In fact, I did too much work here because after opening the device up, I found the word “CONSOLE” printed on the solder mask right next to those ports. After soldering some headers to it, I was able to connect it to my Raspberry Pi and enter the root shell without needing any password. The whole process took about an hour–the most time being trying to physically open the plastic shell because (and this may be surprising) hackers are not the epitome of physical strength.

Once I got a shell, I dumped the flash memory and I grepped for the MAC address printed on the label (trying hex, ASCII, and different separators). I found a file in a partition labeled NVRAM containing the MAC address. The file does not appear to have any checksums, so I just replaced it with a new MAC, rebooted and… nothing. The modem refused to establish a connection. That’s when the real work started…

The first clue was looking around in the NVRAM partition and finding a set of certificates signed for the modem’s MAC address. Googling “DOCSIS certificate” led me down the rabbit hole of modem cloning, service stealing, bandwidth unlocking, and so on. I learned about how not too long ago, people would modify their modem configuration files in order to unlock higher speeds than what they paid for (if anything at all). As ISPs clamped down and secured their infrastructure, the hackers moved on to “cloning” modems by finding the MAC address of an existing subscriber and reprogramming their modem to use the same MAC address in order to steal service. As a result of all this, the DOCSIS 1.1 specification established a PKI system of validation for MAC addresses.

First, I generated a set of self-signed certificates for my new MAC address. Surprisingly, I was able to provision the modem and my ISP accepted the certificate and gave me an IP address. Unfortunately, I was not able to access the Internet and even using my old router’s MAC address did not work. My guess is that self-signed certificated are used by engineers to test the network and therefore do not allow access to the Internet. It likely also has to do with protections against “simple” cloning. Now my plan is to get a new set of certificates from an unactivated device. I went on eBay and bought a broken SurfBoard SBG6580. The reason for this model is purely because it was the cheapest one I could find. Since it was broken, it is more likely that it’s deactivated.

Dumping SBG6580

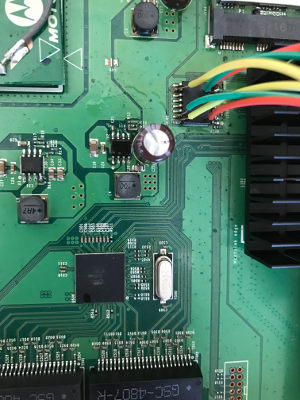

Unfortunately, the FCC does not have the schematics for this device public but a quick inspection showed that the chip labeled Spansion FL128SAIF00 is a 16MiB SPI based flash memory with the datasheet being easily available online. Being a TSOP chip, it is easy enough to solder wires to and luckily I remembered NORway from back when I downgraded my PS3 and that it has SPI dumping support. I connected the Teensy2++ and patched in support for detecting this chip.

binwalk was able to find some embedded certificates

DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL DESCRIPTION

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

67322 0x106FA Certificate in DER format (x509 v3), header length: 4, sequence length: 803

68131 0x10A23 Certificate in DER format (x509 v3), header length: 4, sequence length: 1024

70249 0x11269 Certificate in DER format (x509 v3), header length: 4, sequence length: 808

71063 0x11597 Certificate in DER format (x509 v3), header length: 4, sequence length: 988

83445 0x145F5 Certificate in DER format (x509 v3), header length: 4, sequence length: 866

84317 0x1495D Certificate in DER format (x509 v3), header length: 4, sequence length: 983

85306 0x14D3A Certificate in DER format (x509 v3), header length: 4, sequence length: 864

100090 0x186FA Certificate in DER format (x509 v3), header length: 4, sequence length: 803

100899 0x18A23 Certificate in DER format (x509 v3), header length: 4, sequence length: 1024

103017 0x19269 Certificate in DER format (x509 v3), header length: 4, sequence length: 808

103831 0x19597 Certificate in DER format (x509 v3), header length: 4, sequence length: 988

116213 0x1C5F5 Certificate in DER format (x509 v3), header length: 4, sequence length: 866

117085 0x1C95D Certificate in DER format (x509 v3), header length: 4, sequence length: 983

118074 0x1CD3A Certificate in DER format (x509 v3), header length: 4, sequence length: 864

131164 0x2005C LZMA compressed data, properties: 0x5D, dictionary size: 16777216 bytes, uncompressed size: 2898643604054482944 bytes

8388700 0x80005C LZMA compressed data, properties: 0x5D, dictionary size: 16777216 bytes, uncompressed size: 2898643604054482944 bytes

This includes DOCSIS BPI+ certificates for both US and European regions as well as code signing certificates and root certificates. But unfortunately, no private keys. From experience, it seems likely that the private keys would be stored close to the public keys, so I looked in the hex dump for possible candidates. There were blobs of random looking data in between some of the certificates. It also appears that before each certificate is a two-byte length of the DER file. So I was able to parse the NV storage to dump the certificates, some plaintext setting and device information, as well as 0x2A0 sized blobs of data I previously saw. This data can’t be the private exponent of the RSA key because it is too large. It also does not appear to contain any structure, so it can’t have any CRT component of a key. My hypothesis was that it’s an encrypted PKCS#8 RSA private key in DER format. The evidence was that the file size was aligned to an encryption block, that my other modem used PKCS#8 in DER, and that PKCS#8 DER of an RSA1024 key is about 0x279 bytes, which is suspiciously close to 0x2A0 (for comparison, PEM encoded keys are at least 0x394 bytes and PKCS#1 in DER is almost 1KB because of the extra factors).

Reversing the Firmware

With that in mind, there is no way around having to reverse the firmware. The last two entries in

With that in mind, there is no way around having to reverse the firmware. The last two entries in binwalk showed two large compressed chunks, which is a good start. I found another hacker has dealt with this kind of compression before and the trick was that the header was non-standard (it lacked a valid uncompressed size field). Googling the CPU gave this wiki which asserts that the architecture is big endian MIPS. There were many references to 0x8000.... in the firmware and nothing to 0x7fff...., so I assumed the load address was 0x80000000. Of course, the load address was incorrect but rather than spending time reversing the bootloader, I instead assumed that the load address was page-aligned (because what sane programmer who isn’t thinking about security wouldn’t) and found a random pointer from the code into the large section of strings and incremented the pointer by 0x1000 until I found a string that started at that address. The load address was 0x80004000.

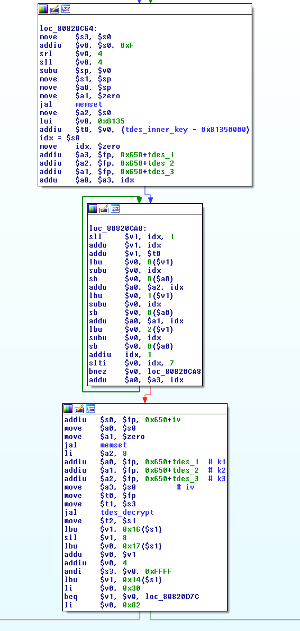

Thankfully there are enough debug strings to narrow down the search for the decryption routine in the 16MiB firmware. By looking for terms like “decrypt” and “bpi” and “private”, I was able to find a function that prints out ******** Private Key Source is ENCRYPTED. (%d BytesUsed)\n as well as @@@@@@@@@ des3ABC_CBC_decrypt() failed @@@@@@@. Seems pretty promising.

From the debug printf, it’s obvious that some blob of data is passed to a function called des3ABC_CBC_decrypt. I assume this means 3DES EDE with a 3-key config. The input key is 21 bytes which is non-standard. Turns out there’s a simple key derivation process (yay security by obscurity) that involves shuffling the key bytes, and subtracting the index from each byte. Then the 21 byte key, which is 8 groups of 7 bits is transformed into the standard representation of 8 groups of 8 bits where each group has a parity check. I’ve included the reversed code below.

With the correct key, I was able to decrypt the 0x2A0 blob which turned out to be (as I suspected) a DER encoded PKCS#8 RSA private key along with a SHA1 hash to authenticate the encryption.

At last

It was a fun journey, but out of caution, I will not be actually using this modem. Cloning MACs is too much intertwined with stealing internet service and although it is not something I ever intend to do, I do not want there to be any confusions between me, the government, and Big ISP. As a result, it was just a fun exercise. As a word of advice to the reader, many people have been arrested for hacking modems. This site does not condone or promote any illegal activities and this post is presented only for education purposes and is more about reversing hardware then it is about bypassing restrictions.

Other Notes

Here’s some “fun facts” I’ve gathered on my journey.

- Some modems have backdoors for your ISP (usually technician and customer service agents) to log in to. The modem I looked at had a SSH server that is not visible on the LAN (your devices <-> your modem) or WAN (your modem <-> Internet) but is visible to the CMTS (your modem <-> your ISP). This is enforced by iptables. They also have a separate username/password to the router gateway page with a weak password that you cannot change. This login works from LAN and WAN as well if you enable remote management.

- EAE (early authentication and encryption) is a feature in DOCSIS 3.0 that allows an encrypted connection to be established early on. My ISP (one of the top ISPs in America) has this disabled even for DOCSIS 3.0 routers that support it. The CM config file contains information on your service plan, your upstream/downstream limits, your bandwidth usage, and more. This is sent unencrypted along with the DHCP request to establish an IP address.

- Because of the above, it might be possible to perform a MITM attack on neighbors through DHCP.

- DOCSIS 3.0 provides the ability to use AES-128 per-session traffic encryption but my ISP (again one of the top ISPs in America so I doubt other ISPs differ in this) chooses instead to use DES (not 3DES by the way) with 56-bit keys (since they still support DOCSIS 2.0). Note that an attack was presented in 2015 by using rainbow tables to make cracking DOCSIS traffic trivial. Reading the service agreement with my ISP, it seems that they concede to this and declared that there is no expectation of privacy with their service. I guess a legal fix is much easier than a technical one.

Now a picture of you struggling to open a plastic box is forever imprinted in my brain :)

Joke aside, great read as always, thanks! Makes me worried of how many people are accessing my router, a very popular model on a very popular ISP’ s network…

Thanks for sharing, awesome article, next time a heat gun will do the trick for opening the hard plastic.

Reading blogs like this really makes me realize how free my country is. No enforced crappy ISP modems with backdoors and rootkits pre-installed. I can use whatever hardware I want.

Excellent observation yifan.

Charter or Comcastic?

I have a router It does not provide the web settings page (but the 80 port has a web engine, 404 access), and SSH and telnet are open Normally an app is used to control it, and its app seems to send instructions to a server, and my routing device fetches instructions from this server I tried SSH and telnet login, but found that the default password was incorrect Is there any way to obtain shell privileges without modifying the hardware?

That’s nice share which is beneficial for the newbie like me. I look forward to more article on your website. Thanks for the article.

I’ve been developing software for over 25 years. My ISP refuses to let me purchase my own DOCSIS modem and I MUST use their piece of S#IT (POS). I was searching for a way of spoofing the MAC Addr so that I could use my own modem. Even with the 25+ years of software dev what you describe sounds like fun but not simple (not for an old dog like myself anyway). I was hoping for a silver bullet. I’ve tried to ssh into the POS modem but it’s locked down pretty well (probably a result of safeguards against the rabbit hole of modem cloning, etc.) Thanks for the entertaining blog post and a trip back down memory lane back when 4K was considered a lot of memory.

This article is excellent, but at the same time, showede how “out of my league” is all this procedure.

As others posted here, I’m stuck with an old cable modem with DOCSIS 2.0 on it. It’s a good device, but the outdated firmware is giving me hard times with my connection because of the new ways of transmitting the signal.

The tech support is a nightmare here and they can let you down in several ways before solving something.

A lot of times I finally solved the problems on my own.

I wanted, as the article explains, use a new cable modem with my service.

I PAY for it, so I wish it could be like in other countries where you can use whatever you want and they have their controls of the service on the end of their line, no both ways.

So I was about to buy a used cable modem of someone that was client of the same company, but I called them first and they wouldn’t allow me to use other modem (providing the new MAC of course) because of legal issues regarding the contract of the user and the cable modem that the ISP provides to that user, specifically.

Now that I see this article I realize that I don’t have the technical knowledge to achieve this. I was hopping to find some firmware replacement that allowed me to change the MAC with mine and achieve somehow the synchronization with the ISP.

But finally seeing what needs to be done… I will need to fight this with tech support this time.

The “third way” is too difficult for me in this one. :(

THANKS anyway for this awesome article. Very useful!

considering what your article reveals about DOCSIS encryption it does make me slightly more paranoid considering the Security is lax and it’s possible to MITM attack people’s traffic and analyzing it even though MOST of the article flew over the head of my level of technological knowledge I am able to gleam enough technical understanding of it to realize for all the modems on my CMT with SNMP enabled it should be possible to essentially sniff their traffic and launch a rainbow tables decryption algorithm on it and if it’s THAT Simple for anyone with the technological means to do so it makes me that much more paranoid and wanting to use my Private paid for VPN more often because god only knows what my neighbors are capable of and I don’t like being spied on or to think it would be THAT easy to figure out what websites I visit and what I’m doing.

I am in fact thankful to the holder of this web page who has shared this impressive paragraph at here.

I obtained a firmware backup from activated modem, now I want to use that im my modem, model is motorola sbg6580, you can email me at ec513331@gmail.Com

Thank you great writeup

Wow I read this and have no idea what I read I was hoping you just plug your new modem into a computer go to the modems addresses and submask and change them to what the cable providers modem has and that would be simple I can’t imagine trying to do this as it is way to complicated