A friend recently invited me to participate in Foobar, Google’s recruiting tool that lets you solve interesting (and sometimes not-so-interesting) programming problems. This particular problem, titled “Distract the Guards” was very fun to solve but I found no good write-ups about it online! Solutions exist but it is rather hard to understand how the author came upon the solution. I thought I might take a shot and go into detail into how I approached it–as well as give proofs of correctness as needed.

Disclaimer: If you are participating in Foobar (hello googler) or have aspirations to do so in the future, please stop here in the spirit of the challenge. It’s well known that Google has a finite pool of problems so you will miss out if you just read the solution.

To begin, here is the problem statement:

Distract the Guards

===================

The time for the mass escape has come, and you need to distract the guards so

that the bunny prisoners can make it out! Unfortunately for you, they're

watching the bunnies closely. Fortunately, this means they haven't realized yet

that the space station is about to explode due to the destruction of the

LAMBCHOP doomsday device. Also fortunately, all that time you spent working as

first a minion and then a henchman means that you know the guards are fond of

bananas. And gambling. And thumb wrestling.

The guards, being bored, readily accept your suggestion to play the Banana

Games.

You will set up simultaneous thumb wrestling matches. In each match, two guards

will pair off to thumb wrestle. The guard with fewer bananas will bet all their

bananas, and the other guard will match the bet. The winner will receive all of

the bet bananas. You don't pair off guards with the same number of bananas (you

will see why, shortly). You know enough guard psychology to know that the one

who has more bananas always gets over-confident and loses. Once a match begins,

the pair of guards will continue to thumb wrestle and exchange bananas, until

both of them have the same number of bananas. Once that happens, both of them

will lose interest and go back to guarding the prisoners, and you don't want

THAT to happen!

For example, if the two guards that were paired started with 3 and 5 bananas,

after the first round of thumb wrestling they will have 6 and 2 (the one with 3

bananas wins and gets 3 bananas from the loser). After the second round, they

will have 4 and 4 (the one with 6 bananas loses 2 bananas). At that point they

stop and get back to guarding.

How is all this useful to distract the guards? Notice that if the guards had

started with 1 and 4 bananas, then they keep thumb wrestling! 1, 4 -> 2, 3 -> 4,

1 -> 3, 2 -> 1, 4 and so on.

Now your plan is clear. You must pair up the guards in such a way that the

maximum number of guards go into an infinite thumb wrestling loop!

Write a function answer(banana_list) which, given a list of positive integers

depicting the amount of bananas the each guard starts with, returns the fewest

possible number of guards that will be left to watch the prisoners. Element i of

the list will be the number of bananas that guard i (counting from 0) starts

with.

The number of guards will be at least 1 and not more than 100, and the number of

bananas each guard starts with will be a positive integer no more than

1073741823 (i.e. 2^30 -1). Some of them stockpile a LOT of bananas.

Languages

=========

To provide a Python solution, edit solution.py

To provide a Java solution, edit solution.java

Test cases

==========

Inputs:

(int list) banana_list = [1, 1]

Output:

(int) 2

Inputs:

(int list) banana_list = [1, 7, 3, 21, 13, 19]

Output:

(int) 0

Now I love a good story and I love a challenging problem but the two fit together like chocolate and eggplant parmesan but I digress. If you parse through the bananas and thumb wrestling, it is easy to see that this is a combinatorics problem. The first thing to do is to break the large problem into some smaller ones that can be pieced together. Here we see that a key piece is figuring out, for any two given guards, if they will go into an infinite loop or not. Once we figure that out, the second part is to find which guards can be paired into infinite loops such that a maximum number of guards end up in infinite loops. Let’s solve the second part first.

Maximum Matching

Assume we have a predicate \(willLoop(x,y)\) for two guards, each with \(x\) bananas and \(y\) bananas that returns true if the pair will loop. Can we then pair up all the guards optimally so we have the most number of infinite loops? Note once we have this, the answer will be simple: just return the total number of guards minus the number of guards that are paired up into infinite loops.

What if we just brute-force and try to find every possible pairing? We take one guard and try to pair her with another guard and if they don’t loop, we try pairing her with a different guard. This will find us a solution but how do we find a maximum one where the most number of guards are paired off? Well, we can then try to find every possible set of pairings. How long will that take? Let’s say there are \(n\) guards. Then it will take \(O(n^2)\) time to find one set of pairings. To find every possible pairing, notice that once we pair off two guards, those two guards cannot be used to pair with anyone else. So for every pairing in every solution set of pairings, we can remove that particular pair, reassign the remaining pairings, and be left with another potential solution. This means the whole process could take \(O(2^{n^2})\) time to process! Clearly infeasible.

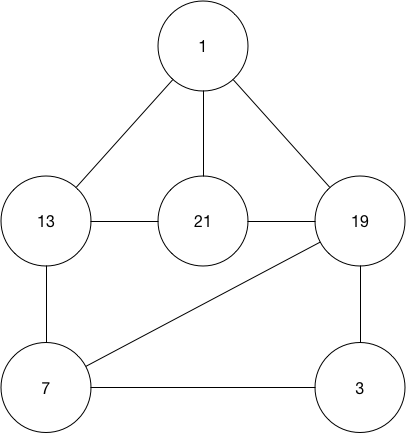

At this point we should take a step back and approach this another way. Instead of trying to find an algorithm to solve this specific problem, we should try to cast it into an existing problem. To do so, we need to find a structure that can hold the problem together. The word “graph” should be screaming at you right now and indeed this looks perfect for a graph: we have a set of guards (nodes) where any two guards are related (edge) by \(willLoop\). Let’s draw out a graph for the second test case.

Here we labeled each node (guard) by the number of bananas they start with. We draw an edge between two guards if \(willLoop\) is true between them. What does it mean to have a set of pairings? If the pairings are a set of edges, that means each node can have at most one edge in the pairing. Here is an example of a set of pairings.

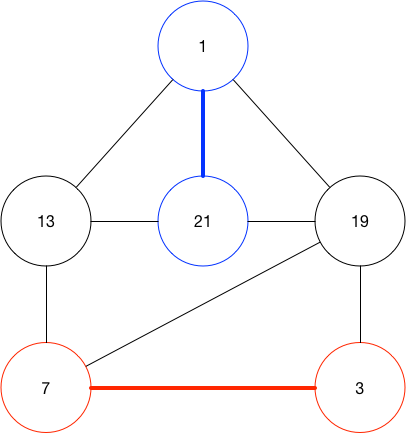

Notice that the guard with 13 bananas and the guard with 19 bananas are not paired with anyone. We cannot select an edge for either of them because doing so means that one of the already colored nodes will have two edges in the solution set, which is not allowed. However, we can find a better set of pairings.

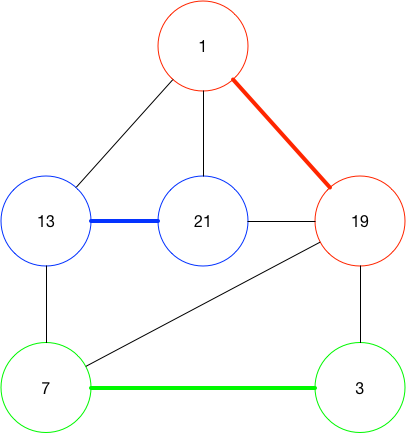

Now every guard is paired up and therefore we know the fewest number of guards that won’t infinite loop is zero. This is a simple example where we can find the solution visually but what if there are 100 guards? What if the solution is greater than zero? How will we know when we reached the minimum and there is no better set of pairings? Most importantly, is it even possible to solve this problem in sub-exponential time (otherwise our solution will be infeasible and we get the dreaded execution time out error)? Turns out these exact questions have been asked by computer scientists for many decades. It is a problem in graph theory called perfect matching, which can be reduced to a closely related problem of maximum matching. Formally, a maximum matching can be defined thus: given a graph \(G=(V,E)\), find a largest set \(S \subseteq E\) where for each \(v \in V\), there is at most one \(s \in S\) such that \(v \in s\). Note I say “a largest set” because there can be multiple sets of equal cardinality that is maximum.

In the 1960s, Jack Edmonds lit the algorithms world on fire by finding a polynomial time (specifically \(O(V^2E))=O(n^3)\)) algorithm to solve perfect matching for any graph. His “blossom algorithm” as it came to be called is not a simple one and I won’t attempt to explain it here. If you want to know more about how it works, it’s presented at an undergraduate level by Professor Roughgarden in these notes. The upshot is that we can apply this algorithm directly to our graph to get the maximum matching. A quick Google search for a Python implementation turns up this page.

Now all that’s left is to define \(willLoop(x,y)\).

Loop Detection

Our intuitive approach will be dead simple: let’s just simulate the game until either it ends or we detect a loop. How will we detect a loop? We could keep a list of “seen counts of bananas” and after each round we check to see if the current counts has previously been seen. If so, we know we are in a loop because the same sequence of banana counts will proceed. Otherwise, at some point we will see both players end up with the same number of bananas. How well does this perform? If \(n\) is the total number of bananas “in play” (the sum of the two players’ banana at the start), then we see that the most number of turns would be \(O(n)\) turns because after \(n\) turns, you would have to either see both players have the same count or see every single count of bananas and therefore must repeat one such count. But \(n\) could be as large as \(2^{30}-1\) so this will not do. It’s sub-linear or bust!

We wish to find a formula (predicate) for predicting the outcome of the game without playing it. To start, let’s just write down a couple of examples and try to find patterns. Below, each line \((x,y)\) is a round of the banana thumb wrestling game where \(x\) and \(y\) are the number of bananas currently in each player’s possession. I’ll list a couple of games below, both with and without loops.

(3,5)

(6,2)

(4,4)

(5,7)

(10,2)

(8,4)

(4,8)

(8,4)

...

(1,4)

(2,3)

(4,1)

(3,2)

(1,4)

...

(3,13)

(6,10)

(12,4)

(8,8)

You can smell the hint of a pattern although it may not be obvious yet. Let’s try to suss out the scent. We know there is some periodic structure (groups, you say?) but how do we go from one line to the next without following the complex rule? Is there an easier way to generate this sequence? Well if at first you don’t succeed, try and change domains. Notice a key fact: the sum of the bananas in each round is always the same. This may be obvious considering no bananas are created or destroyed in each round–let’s call it the Law of Conservation of Bananas. With that in mind, let’s work in \(\pmod n\) where \(n=x+y\). Note that when working with numbers modulo \(n\), negative numbers \(-y\) are the same as \(n-y\).

(3,-3) % 8

(6,-6) % 8

(4,4) % 8

(5,-5) % 12

(-2,2) % 12

(-4,4) % 12

(4,-4) % 12

(-4,4) % 12

...

(1,-1) % 5

(2,-2) % 5

(4,-4) % 5

(-2,2) % 5

(1,-1) % 5

...

(3,-3) % 16

(6,-6) % 16

(-4,4) % 16

(8,8) % 16

Do you see it? We notice two facts. First, by how we defined \(n\), we have \(x=-y \pmod n\). This is a given. The more important fact is that we can see that each round is exactly two times the previous round \(\pmod n\). This seems like an important fact but it doesn’t appear to give us an answer immediately. We also made a lot of assumptions that seems to be unstable and although we might have found a pattern–it might also be a red herring. I am a strong proponent of what I call the 3-examples rule which is: if something works for three random examples you make up, it probably works for all integers. QED. However, until the mathematics community accepts my rule as law, we unfortunately must do things the old fashioned way.

My first tool of choice, as always, is group theory because it’s easy but sounds hard so that maximizes the show-off factor. Let’s formalize this game into a group whose elements can be generated by the group operator. We will see later that the advantage of this is that we can dangle from the shoulder of giants and not have to prove anything major. Lets define group \(\mathcal{G}[n]\) on \(n\) with elements \(e=(x \pmod n, y \pmod n)\) and the operator \(\oplus\) which we will now construct.

In constructing \(\oplus\) we note that the only elements we care about how the operator works for is \((x,y) \oplus (x,y)\) (from here on, we drop the \(\pmod n\) when obvious for brevity). We want to say something like “if we apply \(\oplus\) to \((x,y)\) for \(t\) times, then we get element \((u,v)\) which is the result of playing \(t\) rounds of the banana thumb wrestling game”. We do not care (for now) what \(\oplus\) does to other element pairs. Let’s formalize this

\[\begin{aligned} (x,y) \oplus (x,y) &= \begin{cases} (x-y, 2y) & x > y \\ (2x,y-x) & x < y \\ (x,y) & x = y \end{cases} \\ &= \begin{cases} (x-(n-x), 2(n-x)) & x > y \\ (2x,(n-x)-x) & x < y \\ (x,(n-x)) & x = y \end{cases} \\ &= (2x,-2x) \\ &= (2x,2y) \end{aligned}\]Note we start with the definition of the game and apply the Law of Conservation of Bananas to remove the \(y\) dependency. Then we apply the modulus and simplify to get our final form of \((2x,2y)\). Note this shouldn’t be surprising given our initial intuition. Now comes the point again where we want to turn our problem into something more familiar. It’s easy to see that \(\mathcal{G}[n]\) is a valid group but we want to cast the subgroup generated by \((x,y)\) to be isomorphic to something well known (like the additive group \(\pmod n\)). Why? So we can do cool complex stuff like multiplication and division without worrying about all the pesky details like “is this a ring?”. With that in mind, lets complete the definition of \(\oplus\) to be \((x_1,y_1) \oplus (x_2,y_2) \equiv (x_1+x_2 \pmod n,y_1+y_2 \pmod n)\). You are now convinced that this general definition is consistent with what we have for our special case above.

So it turns out our \(\oplus\) is just \(+\), big deal right? Well turns out this is exactly the additive group \(\pmod n \times \pmod n\), but that is not too important. What’s important is that our subgroup is isomorphic to the additive group \(\pmod n\). I won’t give the proof here because there is little substance but notice that \((2x \pmod n, 2y \pmod n) \equiv (2x \pmod n, -2x \pmod n)\) since \(n=x+y\) by construction. That means we drop the \(y\) dependency. Again, this should all feel redundant because we got to this point from our intuition which gave strong indication that this is correct.

Going back to the game, we see that at round \(t\), we can find \((x,y)^{t}\) by taking \(x \cdot 2^t \pmod n\). Now we can define the predicate

\[willLoop(x,y) = \forall t, x \cdot 2^t \not \equiv n/2 \pmod n\]If this was math class then we would be done. But as programmers, we don’t care about the existence of solutions–we want the damn solution! So how do we get something closed form? With a little manipulation the above turns to

\[\begin{aligned} willLoop(x,y) &= \forall t, x \cdot 2^t \not \equiv 0 \pmod n \\ &= \forall t, \widetilde{n} \nmid x \cdot 2^t \\ &= \widetilde{n} \nmid x \end{aligned}\]Where \(\widetilde{n}\) is just \(n\) with all factors of 2 removed (for example if \(n=112\) then \(\widetilde{n}=7\)). (If you have not seen \(\nmid\) before, it means “does not divide”). Immediately follows is an algorithm for \(willLoop(x,y)\):

def willLoop(x, y):

n = x+y

n_tilde = n

while n_tilde % 2 == 0:

n_tilde = n_tilde / 2

return (x % n_tilde) != 0

It is easy to see that the only work in this algorithm is dividing \(n\) and that happens at most \(\log(n)\) times so this runs in \(O(\log(n))\) time. In fact, for all intents and purposes, this is really \(O(1)\) time since the while-loop is just trimming out the leading 0 bits of the binary representation of \(n\). However, don’t say that to a computer scientist unless you want to be hit on the head with a word-ram-model (pretty heavy).

Appendix A

Here is the full solution without the Python implementation of Edmonds’ blossom algorithm

def willLoop(x, y):

n = x+y

n_tilde = n

while n_tilde % 2 == 0:

n_tilde = n_tilde / 2

return (x % n_tilde) != 0

def bananaGraph(banana_list):

G = {i: [] for i in range(len(banana_list))}

for i, a in enumerate(banana_list):

for j, b in enumerate(banana_list):

if i != j and willLoop(a, b):

G[i].append(j)

return G

def answer(banana_list):

G = bananaGraph(banana_list)

matches = matching(G)

return len(banana_list) - len(matches)

print answer([1, 1])

print answer([1, 7, 3, 21, 13, 19])

print answer([1])

print answer([1, 7, 1, 1])

Neat.

The one thing I don’t like about these story-driven problems is that I tend to read too much into the story and the implied expectations regarding complexity (which is bad as an engineer, but a very good bias as a project manager/tech lead ;)

For example, you mention that the number of bananas could reach 2^30 - 1 because it’s an int. Great. That also happens to be the world production of bananas for one year. How do you buy so many bananas? How do you convince all banana exporting companies to sell and ship those to the prison? Shouldn’t you take into account the life expectancy of the rabbits and the guards when you deal with such insane numbers?

Also, Why the F… is there a doomsday device in this scenario. So many questions, distracting me from the actual problem. :)

I stand corrected. The earth produces 100 billlion bananas a year. You’d only have to purchase 1% of it. Insane.

There’s an easier way to detect an infinite loop. Check the GCD of the pair. For repeating loops the GCD never changes. For terminating sequences the GCD doubles at each step. However there is a third kind of loop to consider. Some have a lead in sequence than doesn’t repeat but eventually turns into a looping sequence. For these the GCD will increase each step for the non repeating lead in part of the sequence, then will become static for the repeating section. So just testing the first and second step of a sequence will not be enough.

We can take this a step further however. If any of the GCDs divide the sum of the pair into a power of 2 then the loop is terminating.

The code looks like this. def test_pair(a, b): sm = (a + b) / gcd(a, b) return not (sm & (sm - 1)) == 0 and sm > 0

Using the function in the article:

willLoop(9, 15) returns true, but in reality it goes (9, 15) -> (18, 6) -> (12, 12) and stops looping.

I kinda just thought, if the sum is odd, they’ll never have an equal number so just look for those pairings. Any time it’s even, it will probably even out eventually. It seems the test cases bear that out. You need at least one odd and one even number to sum to an odd number, and that pairing will lead to two guards distracted. All odd or all even inputs will not distract the guards. Did I oversimplify or misunderstand the problem?

@Linda: You’re right when you write that an odd number of bananas can’t be divided equally, therefore all pairs (a, b) where a+b is odd will lead to a loop.

However, some “even” pairs can loop: (4, 2) → (2, 4) → (4, 2)…

Or (1, 9) → (2, 8) → (4, 6) → (8, 2) → (Loop)…

@Cy: Indeed, the predicate

willLoop(x, y) iff for all t, x * 2^t != n/2 [mod n]is false for (x, y) = (9, 15).The pair (9, 15) does loop but with t=2: 9*2^2 = 36 = 12 [24].

matches = matching(G) What does this statement do?

Jaate Kar (It is how you can continue to augment your graph)

I’d say that Blossom is a bit overkill for this and the Ford-Fulkerson algorithm should be enough and faster: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ford%E2%80%93Fulkerson_algorithm

Forget what I said, it would be true for a bipartite graph which is not the case here.